Below is a guest post by British cultural historian and dear friend, Matthew Ingram.

When I received it just now, I wrote back, “Wow, Matt! I am so honored to see Living on the Earth included in this library of the core books of the counterculture! And I love being your friend and family member in this tribe!!”

________________________________________________________

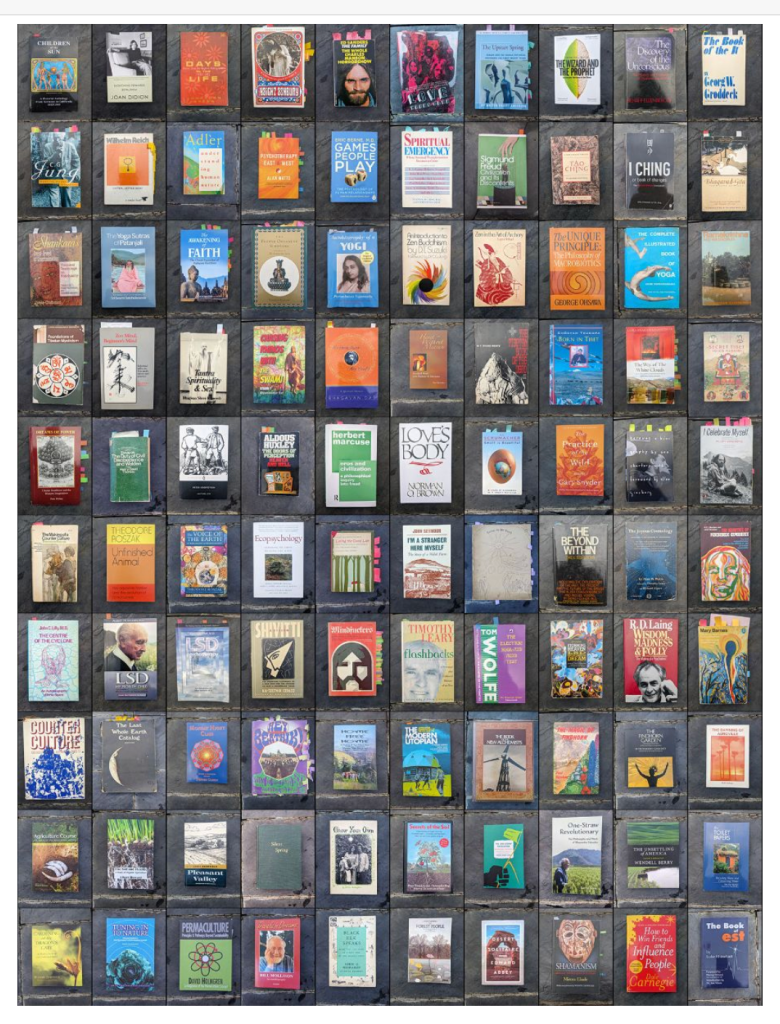

I’ve drawn up a “Sick Veg 100.”

It is comprised of one hundred non-fiction books. They have been selected from the nearly two thousand I’ve read in the past decade.

Twenty years ago at my blog WOEBOT, in December 2005, I made a list of 100 musical records.

For a couple of years I’ve been planning a 100 for the Sick Veg blog, but this time of non-fiction books. I first thought I would do it for Christmas – but I’ve had a little time free – so think of it as an early Christmas present. You’re welcome.

This moment has arrived because I’m clearing my decks. Last week I finally got to the bottom of my pile of non-fiction books. I can date the start of this reading process with accuracy to 15th April 2017 when I ordered a copy of Theodore Roszak’s “The Making of a Counterculture” and begun the research on “Retreat”. Since that date, eight and a half years ago, I must have read close to two thousand books. One book lead to another – in most cases because it referred to another book that I ended up investigating – until the process felt complete…

The books themselves were not expensive, and it’d be inaccurate to think of this as an exercise in bibliophilia, with me showing off my valuable possessions. I was almost entirely concerned with their content. The real cost was the hours I spent reading when I might have been doing other things.

The books here are all ones which made a big impression on me, usually because the ideas they convey are luminous. I’ve broken the one hundred I’ve chosen into the following categories: History, Psychoanalysis, Eastern Philosophy, Tibet, Philosophy, Beat, Theodore Roszak, Self-sufficiency, Acid, Anti-Psychiatry, Communes, Agriculture, Permaculture, Anthropology, and Self-help.

Strictly non-fiction, the list obviously doesn’t include books of poetry (William Blake, John Donne, T.S. Eliot, Allen Ginsberg) or fiction (Charles Dickens, Virginia Woolf, James Joyce, Flann O’Brien, Herman Hesse, Jack Kerouac, William Burroughs, J.G. Ballard, Phillip K. Dick, Thomas Pynchon). But also not writing on music (Simon Reynolds, Lester Bangs, David Toop), on artists (William Blake, Henri Matisse, Paul Klee, Van Gogh, Edward Bawden, Andy Warhol, David Hockney, Jean Dubuffet, Robert Crumb, Moebius, Basquiat, Keith Haring, Brian Bolland, Yayoi Kusama), or practical growing (Eliot Coleman, Charles Dowding, John Jeavons).

Collected together I see these one hundred non-fiction books as the ultimate progressive “Behaviour Change” curriculum.

History.

The books I wrote were histories. So I felt an affinity with these eight. These books – and a few others scattered through this like Jay Stevens’ “Storming Heaven” and Ellenburger’s “Discovery of the Unconscious” are my benchmark for how to write a history; those, and probably Simon Reynolds’ books like “Energy Flash”, “Rip it up and Start Again”, and “Shock and Awe.” I’ve often reflected that I wrote my two published books on subjects other than music because, given Reynolds does it so immaculately, there was no point. It amuses me to think that I’ve treated all the psychiatrists, gurus, and farmers I’ve spoken to as though they were rock stars.

Charles C. Mann: The Wizard and The Prophet

This book was recommended to me by legendary hippie communard Albert Bates. Whenever someone I respect tells me to read to read a book – I make a point of doing it. And in this case I was very glad I made the effort. “The Wizard and The Prophet” – a back-back-back comparison of green revolution pioneer, the arsehole Norman Borlaug, and prototype ecologist William Vogt gave me an invaluable scientific grounding writing “The Garden.” Thank you, Albert.

Walter Truett Anderson: The Upstart Spring

Like many of these books, mine are not first editions or anything fancy. Bought as cheaply as I could find a copy of them. It might be a naff reprint, but this a gripping account of the Esalen Institute’s story and that of the Human Potential Movement. When I spoke to Jeffrey Mishlove about Esalen for YouTube this was fresh in my mind. Reading between the lines I’ve concluded that, after the scabrous “Retreat”, Esalen were uncomfortable about my contributions to their history – although with their coverage in “The Garden” there was something of a thaw in the institutional attitude.

David E. Smith, M.D. and John Luce: Love Needs Care

One aspect of reading the medical and psychoanalytic literature for “Retreat” was experiencing its bracing brutality. The story of the Haight-Ashbury Free Medical Clinic, “Love Needs Care” is a gripping and visceral description of what happened when hordes of maladjusted young people ran away from abusive backgrounds right across the USA, fled to San Francisco, and got juiced on LSD and increasingly harder narcotics. I mean, what could possibly go wrong?

Ed Sanders: The Family

The author Ed Sanders was a member of The Fugs, a favourite band of legendary rock critic Lester Bangs, which were once mentioned in the same breath as The Velvet Underground. This is one of the rare books on this list that I owned long before 2017. I have read it at least twice over the years. There might be more journalistically thorough books about Charles Manson, but this is the one you want.

Charles Perry: The Haight-Ashbury

Charles Perry’s book is an incredibly dense pile up of facts and dates. It is at once a missed opportunity (in lieu of an readable book), and an invaluable chronicle of that moment in time when it felt to a generation that the world might change.

Jonathon Green: Days in the Life (1961-1971)

Green made and brought together engrossing interviews with a whole generation of movers and shakers. It’s an engrossing read which succeeds where the Charles Perry’ “The Haight-Ashbury” stumbled. Thankfully for me, both books were broadly focused on culture, neglecting to explore the currents like meditation, health and farming I examined in my two published books.

Joan Didion: Slouching Towards Bethlehem

Didion’s classic book is impeccable reportage journalism describing the San Francisco scene. Unmissable.

Gordon Kennedy: Children of the Sun

A pictorial anthology of the Lebensreform movement in Germany and the Nature Boys in California by Organic farmer Gordon Kennedy. It features rare and wonderful images from the author’s own collection. I was very grateful to be able to correspond with Kennedy and interview him for “The Garden.”

Psychoanalysis.

After wading through many books by the pioneers of psychoanalysis: Freud, Jung, Reich, Adler, Rank, Maslow, Perls, Goodman, Skinner, Rogers, May, Laing, Janov, and Assagioli – I came away dazzled and intrigued, but convinced it was as more of a religion, with a cadre of high priests, than a science. Undergoing it myself only confirmed that impression.

Stanislav Grof, M.D, and Christina Grof: Spiritual Emergency

The idea of the Spiritual Emergency, which once had a wide currency, was a brilliant observation of psychological breakdown that was influenced by concepts taken from Eastern Philosophy. Especially important to it was the idea of Kundalini, popularised by figures like Gopi Krishna and the psychoanalyst Lee Sannella.

Non-western cultures traditionally saw symptoms of mental illness as signs of evolution of the personality that needed to be carefully streamlined. Psychiatric observations of schizophrenic patients often reveal a fixation upon spirituality. Rather than medicate the subject into a zombie, this generation of psychoanalysts took the risky path of working with and trying to help the subject make sense of their madness.

Eric Berne, M.D.: Games People Play

Transactional analysis is an interesting psychological model which provides us with all kinds of useful insights. The idea of games was huge with the hippies.

Alan Watts: Psychotherapy East & West

I’ve read practically all Watts’ books and thoroughly enjoyed them – but I have a special place in my heart for this. It’s a knee-jerk observation by Vedic and Buddhist practitioners that their religions should not be trivialised and grotesquely simplified as therapies. But that does no justice to the brilliance and complexity of Psychoanalysis or Analytical Psychology. These therapies are, in case no one’s noticed, basically religions in their own right. Watts’ book treads the line very carefully. I have memories reading this as I waited in my car on highway CA-1 till my appointment time at the Esalen Institute.

Alfred Adler: Understanding Human Nature

My foundational understanding of Psychoanalysis is built upon Ellenburger’s magnificent “Discovery of the Unconscious” – and this is where I discovered Alfred Adler. He is accorded the same respect there as Freud and Jung. “Understanding Human Nature” is his most celebrated book and I remember it knocking my socks off.

Wilhelm Reich: Listen, Little man!

I have a raft of Reich’s books. Mrs Ingram gave me this early edition of “Listen, Little Man!” as a present and it is therefore dear to me. It has illustrations by William Steig, whom we know at home less for “Shrek”, than for the devastating “Sylvester and the Magic Pebble”. Reich’s inflation is writ large in this text – and for that alone it is a fascinating document.

Carl G. Jung: Memories, Dreams, Reflections.

I’ve chosen this over something like Jung’s dense “Two Essays on Analytical Psychology” or “Symbols of Transformation” because it’s a more enjoyable read which manages, thanks to the personal insights Jung provides into his own character and history, to convey possibly more profound ideas.

Sigmund Freud: Civilization and its Discontents

This is the one with the highest quotient of interesting ideas. It is famous for Freud’s anonymised conversation with Vedantist Romain Rolland which introduces the idea of “oceanic” feelings.

Georg W. Groddeck: The Book of the It

Groddeck was a major influence on Freud’s thinking. He was a German physician whose ideas on psychosomatic medicine were articulated around the same time as the foundation of the psychoanalytic movement. Groddeck, like many intellectuals of his day before World War One, regrettably held ideas that were proto-Nazi and from eugenics. However, they don’t feature in this book which came out in 1923 and is enchantingly bonkers. The story of the wen on his neck always fascinates me.

Henri F. Ellenburger: The Discovery of the Unconscious

This is a tour de force. It is a history which tracks the currents in “primitive” societies and hypnotism into the work of Freud, Jung, and Adler. The idea of the unconscious, which once had some scientific credibility, has been downgraded somewhat into the idea of automatic thinking – but that’s boring! I feel the same way about dreams. Not mystical? Just wish fulfillment? How boring and reductive to think that…

Eastern Philosophy.

When I’m asked what the counterculture was, I’ve got in the habit of saying that it was the influx of ideas of the Vedas, Buddhism, and Taoism into Western culture. That is a surprisingly accurate description. It also sets up the counterculture as part of a continuum predated by movements like Theosophy. Reading these books, a very tiny selection of the many I checked out, was a real mind opener.

Ravi Ravindra: Heart without Measure

Gurdjieff was a philosopher mystic who died in 1949 but whose teachings, the popularity of which peaked in the seventies, are still followed. Truthfully he’s more like a near-eastern philosopher – and his teachings, although they build on Eastern Philosophy, take the ideas in more practical directions.

This book, by Ravi Ravindra, was mentioned to me by sustainable agriculture legend Patrick Holden. Gurdjieff’s autobiography, the entertaining “Meetings with Remarkable Men”, gives one very little insight into what “the Gurdjieff work” entails. But this delightful book by Ravindra provides one with a good feel for it, and is clearer than writings by either of Gurdjieff’s front rank disciples Madame de Salzmann or Pyotr Ouspensky.

Bhagavan Das: It’s Here Now (Are You?)

Bhagavan Das has been neglected by history. Richard Alpert, Timothy Leary’s sidekick, who is known as Ram Dass appropriated his style and his ideas – including the phrase “Be Here Now.” This is a raw and compelling autobiography full of great, eye-popping stories and insights; a roller-coaster read. I regretted some remarks I made about Baba in “Retreat” but he never seemed to mind very much, and I got to make amends in “The Garden”.

Shyamasundar Das: Chasing Rhinos with the Swami

This is Sam Speerstra’s fly-on-the-wall account of living and working with the Hare Krishna guru Pradhupada. His astonishingly detailed reminiscences suggest he must have kept a diary at the time.

Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh: Tantra Spirituality & Sex

This the Osho of the Netflix documentary, “Wild Wild Country.” It is a creepy, tiny book rounding up some of Rajneesh’s thoughts on sex.

Shunryu Suzuki: Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind

Shunryu Suzuki was an important conduit of Zen ideas into America. He was Roshi of the Tassjara Mountain Centre in the Big Sur area – a stone’s throw away from Esalen. This is a collection of his talks that convey his cheerful and friendly nature and his profound insights into the nature of Zen.

Lama Anagarika Govinda: Foundations of Tibetan Mysticism

Born Ernst Lothar Hoffmann in Germany, Lama Govinda was the prototypical modern interloper into Eastern Philosophy. This book is a celebration of the Om Mani Padme Hum mantra – an entire book dedicated to the mantra you see illustrated on its pop-art cover. Lama Govinda’s “Way of The White Clouds” travelogue account of Tibet as it was before Chinese occupation is essential reading and of more general interest..

Christopher Isherwood: Ramakrishna and his Disciples

My adorable godfather Paul, who knew “Little Nick” Drake as a child, and told me an amazing story about Mahesh Maharishi Yogi trying to score weed off him, spent time with the Englishman Isherwood (author of “Goodbye Berlin”) in Los Angeles. He referred to me of Isherwood’s fascination with “his Indian stuff.” Reading this book felt like one of the most far-out peninsulas of my research. Ramakrishna and the accounts of his samahdi are remarkable. The book is suffused with an unearthly aura.

Swami Vishnudevanada: The Complete Illustrated Book of Yoga

I’ve shared this book before in a piece I wrote for The Quietus – and in a post here on the Sun Salutation. This book was one of the most important conduits of Hatha Yoga into the West. Vishnudevananda gave a copy to George Harrison on the set of the movie Help!

George Ohsawa: The Unique Principle

George Ohsawa was responsible for popularising what he called the Macrobiotic diet. This was incorrectly interpreted by the hippies as a call to exclusively eat brown rice. Ohsawa pumped out a staggering amount of books. Many of them, which are no more than articles, are written seemingly off-the-cuff, and lack substance. This was his first book for the prestigious French Vrin publishers in 1931 and it’s both thorough and well-written. It contains my favourite, and I feel most accurate, description of the significance of the principle of the Tao. I like it that Ohsawa put food on the same pedestal as these metaphysical observations.

Eugen Herrigel: Zen in the Art of Archery

Zen snobs, of which there are no shortage, dispute Herrigel’s guru’s Zen credentials or even Zen being the teaching he received. But from what I understand of Zen what’s described works perfectly within its schema, makes for a lucid exposition, and is a nice story. I think of this daily with a little game I play with myself putting our cooking knives into their wooden block. Can I, at a distance, insert the knife into its slot?

D.T. Suzuki: An Introduction to Zen Buddhism

The Jung foreword is the hallmark of your superior Eastern Philosophy, penning them as he did for this book, Heinrich Zimmer’s “Life and Work of Sri Bhagavan Ramana Maharshi”, Evans-Wentz’s translation of “The Tibetan Book of the Dead”, Richard Wilhelm’s translation of the “I-Ching”, and for the Taoist text “The Secret of the Golden Flower”. If I can make a fast and loose comparison, it is akin to the Brian Eno production between 1973-84. D.T. Suzuki gives a very nice introduction with this excellent book.

Paramhansa Yogananda: Autobiography of a Yogi

It turned on George Harrison, Elvis Presley studied it, and Steve Jobs instructed everyone be given a copy at his memorial service. Justifiably famous, it still surprises me that people read this and claim on the back of it some kind of spiritual initiation. Because, although it’s full of useful descriptions and evocations of the Yogic life, it’s notable for its often hilarious tittle-tattle and tall stories. Adorable.

Thomas Cleary: The Flower Ornament Sutra

Just as with the Jung foreword, the D.T. Suzuki foreword is another one to look out for. Thomas Cleary, who must have nearly gone round the bend translating this behemoth into English, describes it thus, “the most grandiose, the most comprehensive, and the most beautifully arrayed of the Buddhist scriptures.” This book is the most staggering omnibus – and I’ve included here for its astonishing iridescence and fecundity. Millions of Buddhas in billions of galaxies. Somewhat akin in ambition to Minimalist musician La Monte Young’s “The Well-Tuned Piano.”

Asvaghosa: The Awakening of Faith

Another book which D.T. Suzuki had a hand in. A beautiful and succinct description of Mahayana Buddhism which I remember being delighted by.

Sri Swami Satchidananda: The Yoga Sutras of Patanjali

I was poised to also include Swami Prabhavananda and Christopher Isherwood’s “How to know God” – another beautiful rendering of Patanjali – before I spotted the duplication. This is nice because of Satchidananda’s connection to the counterculture. I used the information on “herbs” from this.

Viveka-Chudamani: Shankara’s Crest-Jewel of Discrimination

The most hardcore of all the Hindu texts of the Vedanta in this list. It represents the furthest extension of these “etheric”, body denying ideas. Exquisitely lovely but abandon hope all who enter here!

Swami Prabhavananda and Christopher Isherwood: Bhagavad-Gita

The Gita. Which features an introduction by Aldous Huxley, no less. Looking at this copy just now, it’s nothing special, and probably cost me £1, I am nevertheless alarmed to see my highlighting done in a red biro. This is an abhorrent practice which I did when first reading and researching material. If you underline a book, and please do because it’s a valuable practice, ONLY EVER UNDERLINE IN PENCIL.

Richard Wilhelm: The I Ching

I’ve written a very large piece here about the I Ching so check that out.

Stephen Mitchell: Tao Te Ching

This and the “I Ching” are the key texts of China’s Taoist religion. Zen is regarded as a synthesis of Buddhism and Taoism. In reality all of the Eastern philosophies run together as a continuum. A ‘Nuum?The most obvious example of this is that the Buddha was a Hindu.

Stephen Mitchell was widely criticised for this because he didn’t translate from the Chinese and piggybacked a host of other translations. More “authoritative” translations abound – I have two, Red Pine’s and R.B. Blakney’s – neither of which work for me. This on the other hand is perfection. If it’s good enough for Huston Smith, it’s good enough for me.

If there was one book you bought of this 100 let this tiny pocket edition be it.

Tibet.

As both Lama Govinda and Robert Thurman point out, only the Tibetan Buddhists kept faith with the idea that what Buddhists refer to as “Enlightenment” was possible. In the Sri Lankan Buddhist system no one was supposed to have experienced it for thousands of years. The significance of this can be understood in the context of unusual psychiatric states and, although I don’t condone or endorse them, psychedelics.

Reading about Tibet is fascinating because at the time these books were written, before Tibet’s invasion by China, the country was a hyper-evolved Medieval state. The Lamas, religious leaders, ruled the country, and the society’s mechanism was geared around, not the acquisition of capital, but prayer. The monasteries were enormous and dominated the cultural landscape in the way that, for instance, brands like Apple, Google, and Facebook do today. This might seem bizarre, but objectively, why not run a society like that?

Peter Bishop: Dreams of Power

I’ve no idea how I came across this book but it’s an absolute belter. I would hope that in the future people would discover my own books, languishing as they do in relative obscurity, and appreciate them in the same way as I loved this.

Fosco Maraini: Secret Tibet

There are a handful of books describing life in Tibet before 1959 when the Dalai Lama fled the country. Some written by foreigners, and some by Tibetans. They include Heinrich Harrer’s “Seven Years in Tibet” (a very popular book which my mother read as a child), Lama Govinda’s “The Way of The White Clouds”, Alexandra David-Neel’s “Magic and Mystery in Tibet”, Lama Kunga Rinpoche’s “In the Presence of my Enemies” and the two listed in sequence here. They are all excellent. Paul Hawken referred to “Secret Tibet” in his book “The Magic of Findhorn” and it’s outstanding. I plan to have this passage from it read at my funeral.

Chogyam Trungpa: Born in Tibet

As a personality Trungpa is at once repulsive and fascinating. His “Cutting Through Spiritual Materialism” book is heralded as a classic but its simple message – don’t get attached to what you perceive to be spiritual accomplishments – is worthwhile but also slightly banal. However, “Born in Tibet”, an autobiography of his early life and his perilous escape from Tibet is excellent.

W.Y. Evans-Wentz: The Tibetan Book of the Dead

I first read, not this book, but Gyurme Dorje’s later translation of the entire Tibetan Book of the Dead. I did tend to avoid obsessing on owning the correct edition but I did want to have this book pictured above which is Evans-Wentz’s classic translation. This is only a fragment of the Book of the Dead, one chapter called “The Great Liberation by Hearing.” It would have been the copy that Allen Ginsberg would have read as it was passed around the Chelsea Hotel; which Leary, Metzner, and Alpert would have turned into their ridiculous “The Psychedelic Experience”; and which Jung interpreted.

Philosophy.

This title is a bit of a stretch. In case you think I am a bit stupid I should point out that I did read some “proper” philosophy in this period: Plato, Plotinus, Spinoza, Nietzsche, Kant, Bergson, Schopenhauer, Sartre, Deleuze, etc. Blokes known by their surnames. I also read some theoretical thinkers: William James, Alexis Carrel, Marshall McLuhan, Erving Goffman, Christopher Lasch, Susan Sontag, Michel Foucault, Arthur Koestler, etc. But these listed below were the books that I felt contained a transformational message about our relation to the world.

E.F. Schumacher: Small is Beautiful

A friend of John Seymour’s, a great thinker, pioneering ethical businessman and, as I found out recently, an early president of the Soil Association. Profits from this very popular book were left to that organisation by his estate. Schumacher was interested in Eastern philosophy and “Buddhist Economics” is one of the ideas he explores here. I wonder if my old friend Mark Fisher knew about this book? It has many points of comparison with his “Capitalist Realism”. Oh dear – an unbelievably bad cover on this reissue. I wish I had a better edition.

Norman O. Brown: Love’s Body

This is dense Freudian-Marxism with an intensely mystical inclination. It is full of very strong and novel ideas. Norman O. Brown is the missing link between Jim Morrison (who loved his writing) and Alan Chadwick (the gardener of legend he admired at UC Santa Cruz where they were both on the faculty).

Herbert Marcuse: Eros and Civilization

Even denser Freudian Marxism, but well worth getting to grips with. Marcuse was the star turn at the Dialectics of Liberation Congress, the event of its year, in Camden’s Roundhouse in 1967.

Aldous Huxley: The Doors of Perception/Heaven and Hell

This is Huxley’s famous book describing his trip on mescaline with Humphrey Osmond and its aftermath. A great deal of the text refers to Eastern Philosophy – establishing those ideas as the means through which the psychedelic experience was understood.

Peter Kropotkin: Mutual Aid

The exiled Russian anarchist’s book looks at the commonplace presence of mutual aid within species. I used Kropotkin’s “Fields, Farms, and Factories” in “The Garden” and read this book subsequently. “Mutual Aid” is often referred to – but I suspect rarely read, and it’s a wonderful book. My view on the topic is that, while nature and human society isn’t entirely at Tennyson put it, “red in tooth and claw”, that must be at least half the picture.

Henry David Thoreau: The Duty of Civil Disobedience and Walden

The first essay describes Thoreau’s experience of incarceration by the state for not paying a tax, the second, his account of living freely in the common woods outside Concord, Massachusetts. Interestingly Thoreau never actually practiced what we know as self-sufficiency – but he came within a whisker of it. I’ve always loved “Walden”. I made a comic of a section of it in 1997. And in September 2023 I finally visited the pond myself.

Beat.

William Burroughs’ writing is commonly understood as being Sci-Fi of a kind – especially books like “Nova Express” and his response to Scientology “Cities of the Red Night”. In hand with that genre is the idea that the fiction is an attempt to imagine futures. However besides Burroughs, all the best Beat literature, Ginsberg’s “Howl”, “Kaddish”; Kerouac’s “On the Road”, “The Dharma Bums”, and “Big Sur”, chafing as it does against the conventional behaviour and morality of the day, was a kind of Sci-Fi too – pondering alternatives. To that extent I think of it as honorary non-fiction writing – especially Kerouac’s writing which is thinly disguised stories about his life. But rather than fudge anything exclusively for the beat oeuvre by including their writing here as non-fiction – I’m sticking to the plan.

Bill Morgan: I Celebrate Myself

Ginsberg is the man! If there’s one person who embodied the counterculture it is Alan. He straddled both the Beat and Hippie generations. I use Alan for my timeline for the counterculture: It starts with his reading of Howl in 1956 – and ends with his removal from the bill and downgrade to baggage handler by Bob Dylan on the Rolling Thunder Tour in 1975. Between him and Gary Snyder you’ve got it covered. Bill Morgan’s huge biography is excellent and a very satisfying read.

Ann Charters: Kerouac

A good read. Written by someone close to Kerouac, the beat author, who understood and was sympathetic to him.

Gary Snyder: The Practice of the Wild

The poet and ecologist Gary Snyder is immortalised in Kerouac’s “The Dharma Bums” as Japhy Ryder.

Recently I have found myself in situations in which I have explained the significance of Snyder’s ideas in “The Practice of the Wild” to people. Personally, I think they are some of the most incisive and profound I have ever encountered. But for some reason, and I don’t think it is my fault, people don’t get it.

I reason that it’s because many of us are so radically disassociated from the reality of our food – and at such distance from lives lived in nature. We are at the end of long tunnels and never question what is happening at the other end of them.

Snyder deconstructs this alienation by drawing a comparison between what is “wild” – in our poetry, music, art – what is “wild” in our behaviour, dancing, singing, talking to animals, dreaming, madness – and what is “wild” in nature and in our work with natural processes when managing an ecology sustainably or growing biological food.

What’s useful for me is that the idea of “the wild” serves as a way to understand unfamiliar rural practices as being the same as others we are familiar with in an urban cultural context. So growing organic food is the same thing as raving to Jungle. If only more people did get it.

This book could equally be filed under my headings “Philosophy” or “Agriculture” but I kept it here to keep Allen and Jack company. Ironically, Snyder has tried to put water between himself and the other beats.

Theodore Roszak.

I wouldn’t say that I was obsessed by Theodore Roszak, an academic and novelist who died in 2011, but I’m definitely curious as to how he managed to outline the significance of that unique cultural moment in such depth. What was his own background that he cottoned on to all these implications? I wondered whether he might have had some “oceanic” experience of his own and I asked the New Age videographer Jeffrey Mishlove, who knew Roszak and his wife Betty about this, but apparently not.

Although the counterculture implied a lot, and connected up to manifold revolutionary currents, I know a lot of the young hippies weren’t aware in any detail about these wacky traditions they had suddenly embraced. Certainly the elders, and to a greater extent the neurotic but literate Beatniks were aware. Thank goodness there was someone articulate like Roszak around.

Theodore Roszak: The Making of a Counter Culture

This is where it all started for me, and where the coinage “counterculture” comes from. Now it’s known as one word not two as you see on the cover. It’s a dense book, not exactly a fun read, and I imagine a lot of people who bought it were bummed out by its dry academic tone. Still, it’s all laid out here.

Theodore Roszak: Unfinished Animal

A much better edited and more entertaining book than “The Making of a Counter Culture”. “Unfinished Animal” tracks the counterculture into the New Age and looks at how it refracted, as though through a prism, into a panoply of religious affiliations, cults, and therapy and self-help factions. This book should be more widely known.

Theodore Roszak: The Voice of the Earth

This book was the flotation of Roszak’s Ecopsychology concept – his second great coinage. It might seem mysterious that someone who defined the counterculture went on to write about the ecology. What do they have to do with one another? It’s more than the fact that the hippie generation adopted the ecology as one of its prime causes. If you follow the logic of the Eastern Philosophy that the counterculture adopted, especially Taoism (which Roszak argues was reinterpreted in Gestalt Psychology) and Mahayana Buddhism (be it the schools of Zen or Tibetan Buddhism) – then, as is indicated by these ideas, we are of a piece with our environment – and should therefore be preoccupied with it. A widely-heralded book at the time in 1992.

Theodore Roszak: Ecopsychology

A very useful collection of essays. My highlights being by one Stephen Harper, founder of the Esalen Institute Hot Springs Farm who I interviewed for “The Garden”; and there’s an excellent piece by Ralph Metzner, the most interesting thinker of the trio of academics that came out Harvard’s LSD experiments.

Self-sufficiency.

Considering the question of self-sufficiency and its possibility is a first step where the city dweller comes to terms with fundamental realities they hadn’t previously considered. Self-sufficiency is not typically something country folk set out to achieve – and accordingly there aren’t many examples of that happening historically. It is more of a philosophical readjustment than a practical reality. That is in no way to deprecate people trying – because if only everyone would experiment with it to see what the practice reveals!

Unless undertaken with virtuosity, true self-sufficiency leads to a brutal, threadbare existence. It’s probably not to be attempted outside of an interlocking community of small-holdings. In such a conglomeration different groups undertake separate tasks such as: animal husbandry, vegetable growing, and grain production etc.

Although it sounds hilariously pretentious (shrugs) I think of the food growing I do on my rooftop in London as a spiritual practice and relating only to self-sufficiency’s philosophy not any practical concerns. That’s another way of saying that it isn’t meaningful in any productive way – but provides plenty of food for thought.

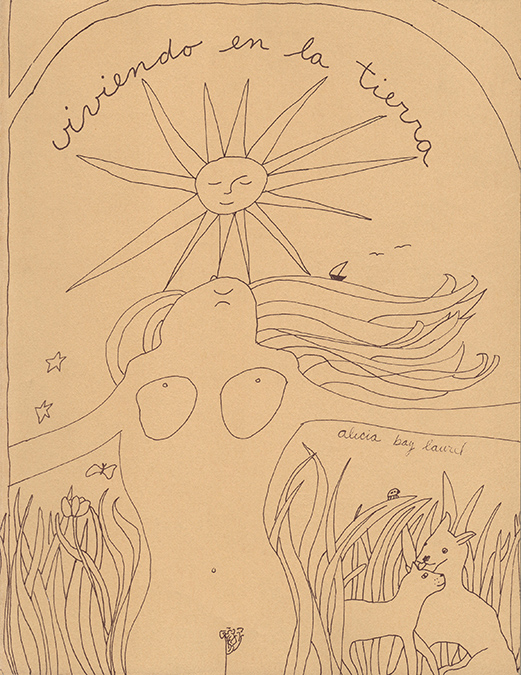

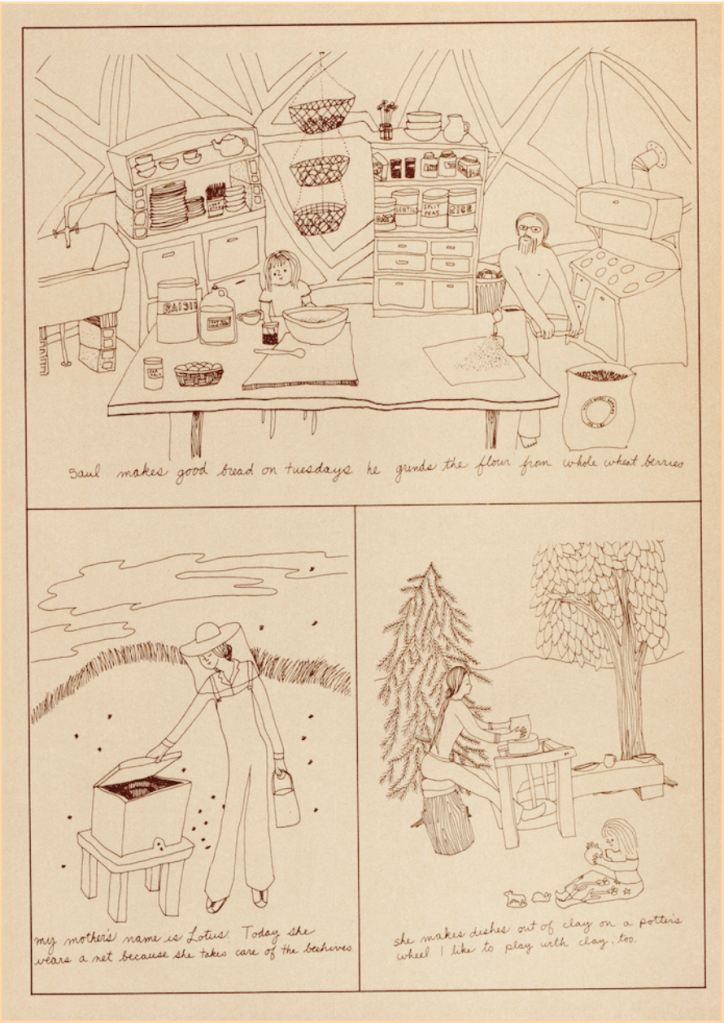

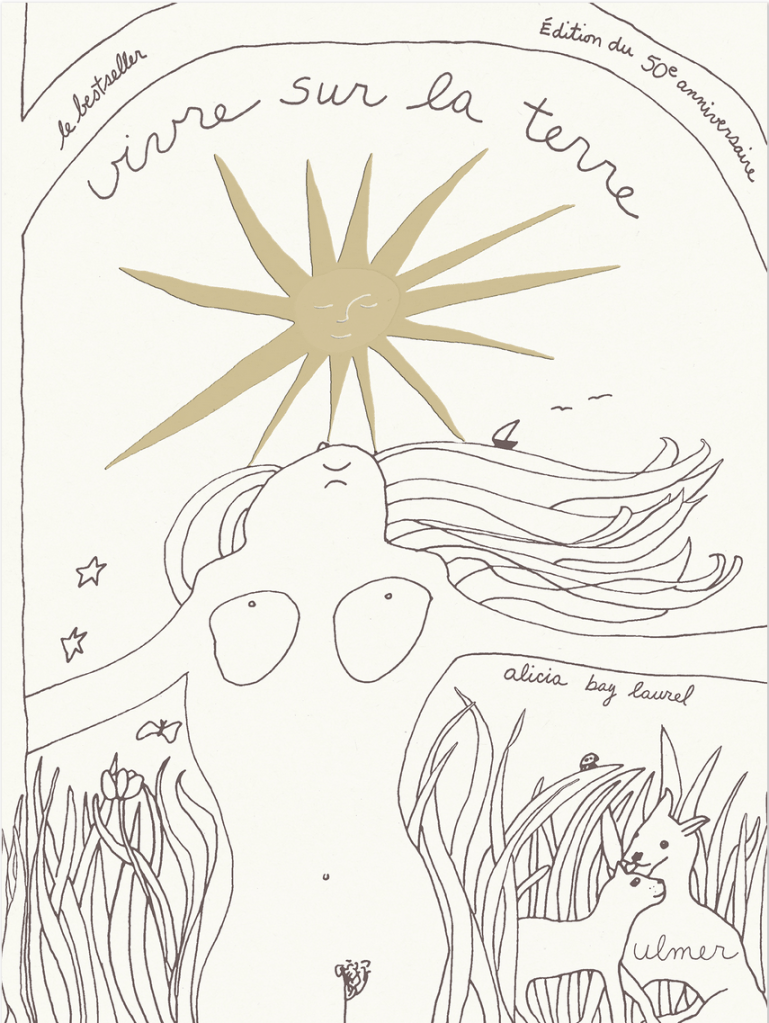

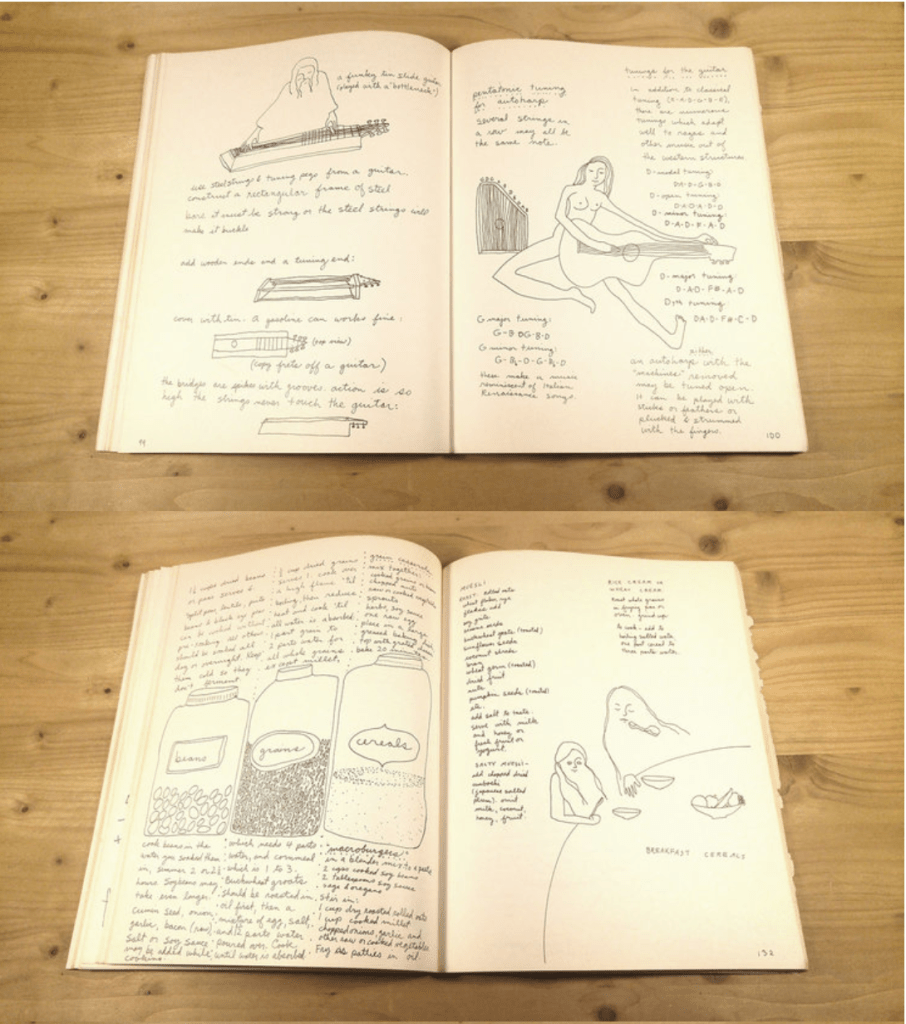

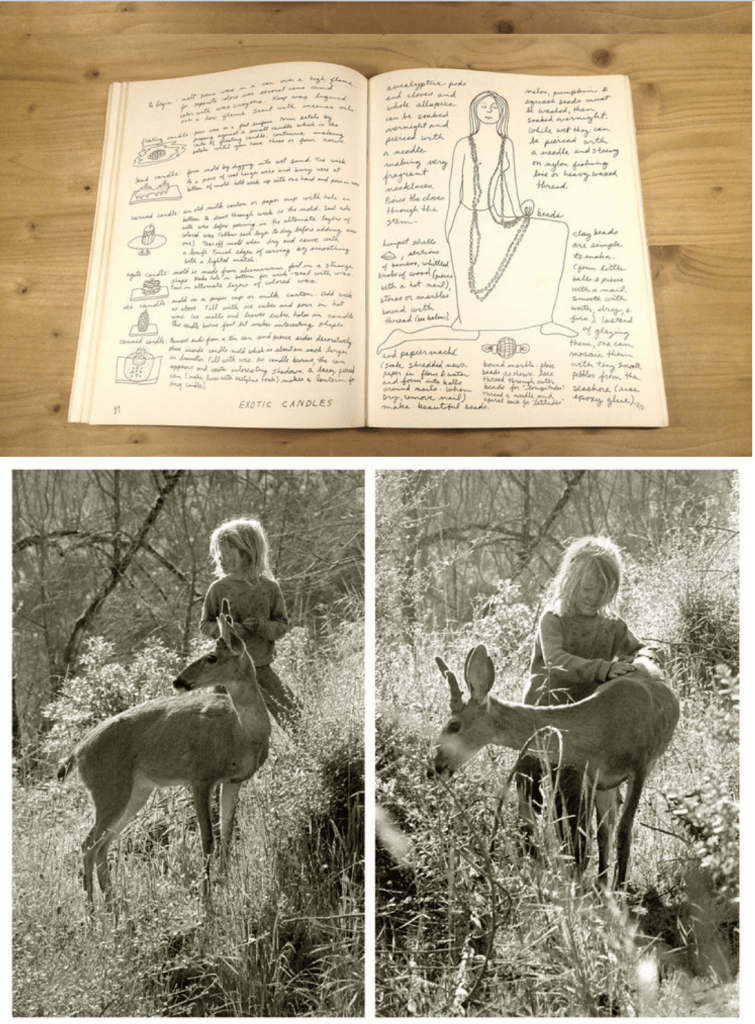

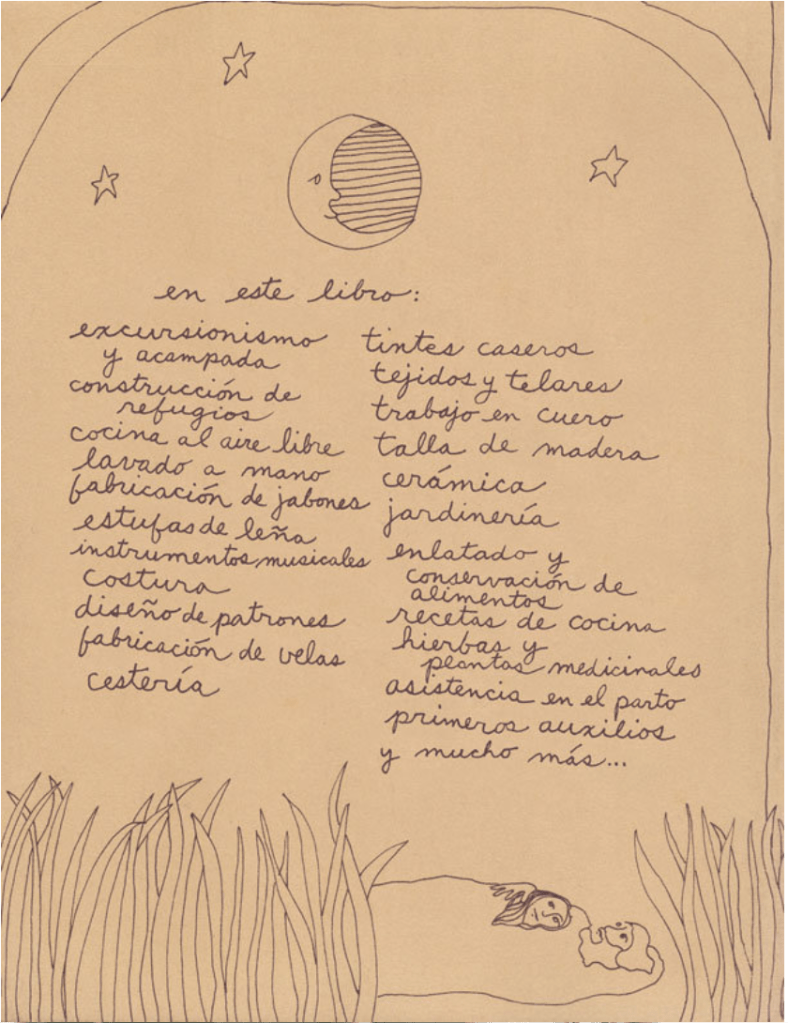

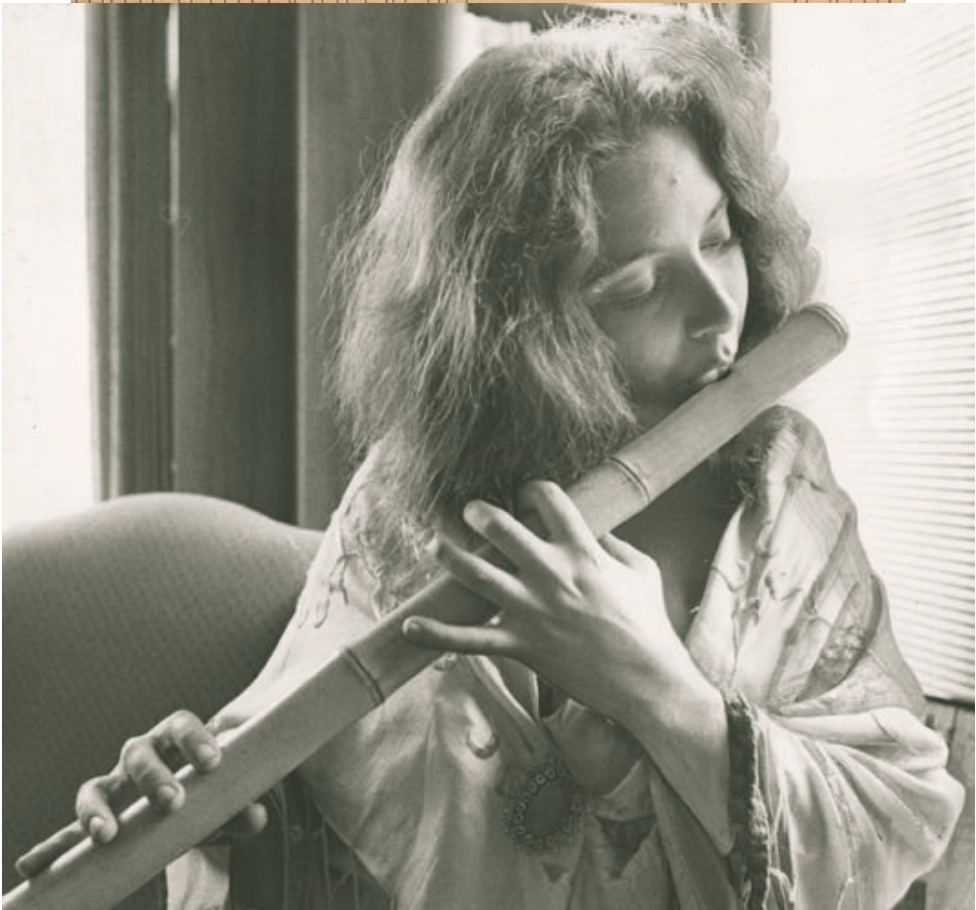

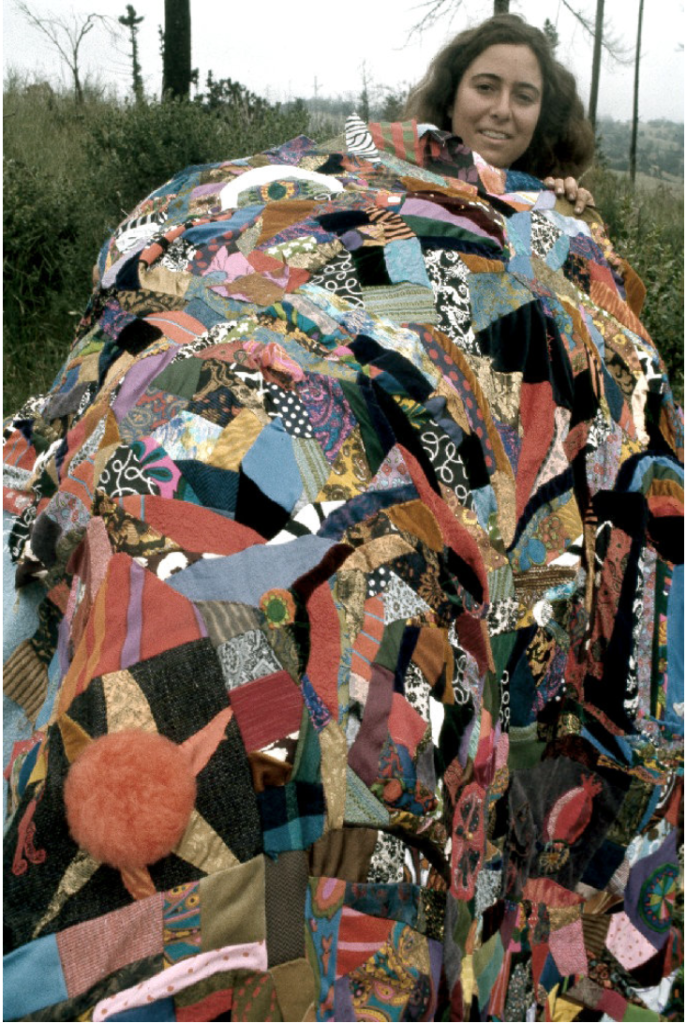

Alicia Bay Laurel: Living on the Earth

I picked up a copy of this wonderful illustrated guide book to self-sufficiency when I was researching “Retreat” – but at that stage didn’t see where it was going to fit into the eventual scheme that unfurled with “The Garden.” Written by the communard Alicia Bay Laurel at Ahimsa ranch, the story of which is mentioned downthread here in the book “Home Free Home”, it depicts a kind of far-out, naked self-sufficiency.

I remembered the book from my childhood, because my mother’s best friend, a Canadian woman, had a copy which she kept in the bathroom. She and her husband also had a Penguin Cafe Orchestra album on cassette. You know the scene. At our home there were only 19th century watercolours and Beethoven – so this was pretty refreshing.

When I eventually got to interview the inspirational Alicia Bay Laurel for “The Garden” it was a massive kick. Words can’t really do it justice to the delights of “Living on the Earth” and its sequel “Being of the Sun” – track down copies if you can.

John Seymour: I’m a Stranger Here Myself

In this new universe I have been imagining – the counterculture, rather than being progressively pulverised through the seventies and left on life-support in 1984, flourished. After the oil shocks of the seventies we all took stock of the ecological implications of our greed for cheap energy and adjusted to a graceful descent. The ideas of Eastern philosophy and indigenous peoples were further popularised and heeded. Just as the hippies weaned themselves off psychedelics and onto religion, right across society stimulants were increasingly kept in abeyance. Consequently madness became untarnished, was streamlined and blossomed into peaceful spiritual practice. Instead of coalescing into ever larger industrial units, farms broke down into smallholdings run by growing numbers of urban fugitives. Even if eaten, animals were loved and respected. Everything appropriate was composted. And there’s a big statue of John Seymour in Parliament Square.

All of Seymour’s books are wonderful. I have read eight of them. “I’m a Stranger Here Myself” might just be wisest, craziest, wildest, and funniest of the lot – and so I recommend it on those terms.

Helen and Scott Nearing: Living the Good Life

Huge in the USA. Practically unknown in the UK. Their roots in, respectively, Theosophy and Socialism make for the perfect background when representing the self-sufficiency they practiced. Originally written in 1954 this is the edition from 1970, which was when the book became wildly popular, and has an introduction by countercultural commentator Paul Goodman.

Acid.

I am no fan of any kind of drug – and I don’t touch any stimulants at all. But, with the right perspective on it, the history and effects of Acid are fascinating. LSD teaches you very little if you have an understanding of philosophy, mental “illness”, and spirituality – but the way that it forces these three issues into the popular landscape is remarkable.

Jay Stevens: Storming Heaven

Please read my eulogy for Jay Stevens here. This book is a stone classic.

On the subject of LSD, in conversation with me, Jay referred to Aldous Huxley’s fictional drug from his book “Brave New World”, a panacea for the modern society: “LSD is soma.”

Tom Wolfe: The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test

This very well known book of documentary journalism describes the first public experiments with LSD when the drug was still legal. It is a valuable profile of Ken Kesey and the Merry Pranksters. Wolfe’s later documentary journalism I can give or take.

Timothy Leary: Flashbacks

I don’t like Leary at all. I think he was a bad egg. But this is still great fun and fascinating.

David Felton: Mindfuckers

I got this especially for the piece on Mel Lyman – a minor singer-songwriter who turned into a spooky home-grown guru. “Mindfuckers” covers the first generation of inflated creeps that LSD produced – and there has been no shortage ever since.

Ka-Tzetnik 135633: Shivitti

An extreme book which describes a failed attempt to use LSD to process Holocaust trauma.

Stanislav Grof M.D. : LSD Psychotherapy

In this book the pioneering psychedelic therapist who found a use for Albert Hofmann’s “problem child” (see below) lays his theory out in full. Here it was a toss up between this and Grof’s earlier “Realms of the Human Unconscious”. I think the latter has more terrifying, and therefore more interesting, trip reports but this does more justice to his system.

I was always a little unsure about including Stan Grof within the context of the counterculture. Because, unlike some of the other acid psychiatrists of the day, he appeared to operate at a distance to it. But to refer to field theory, I would argue that, suit or no suit, the counterculture was the “ground” that created Grof’s “figure.”

Albert Hofmann, Ph.D.: LSD My Problem Child

This is the very gentle and profoundly authentic scientist Albert Hofmann’s autobiography. He was the discoverer of LSD. I particularly relished his account of childhood satori in a Swiss forest.

R.E.L. Masters and Jean Houston: The Varieties of Psychedelic Experience

Jean Houston is a particularly interesting person. Improbably, she befriended Catholic mystic Teilhard de Chardin when she was a child. This book riffs on the title of William James’ “The Varieties of Religious Experience”. It is a large collection of interesting and colourful trip reports.

Alan Watts: The Joyous Cosmology

Timothy Leary and Richard Alpert delight in recruiting the ex-pat English Zen Buddhist Watts to their cause.

Sidney Cohen: The Beyond Within

A very early book on LSD written by an actual adult. So, refreshingly, the book has none of the derangement, inflation, or superstition which is the hallmark of most of the LSD literature.

Anti-Psychiatry.

I inadvertently became something of an authority on Anti-psychiatry. I interviewed two of its leading figures, the dear Joe Berke (who has since died), and the charming Morton Schatzman. I visited Kingsley Hall. I watched the Dialectic of Liberation videos. I read a stack of books by Laing, Berke, Cooper, Szasz, Goffman, Foucault etc. I even went as far as nearly signing up to become a therapist at The Philadelphia Association. There’s a pretty good interview with me here on the subject. I didn’t know it was being filmed so I’m more comfortable than usual.

Joe Berke: Counter Culture

A juicy snapshot of the peak countercultural era by Joe Berke. I only found out recently that Theodore Roszak came to London and lectured at Joe’s “Antiuniversity.”

Mary Barnes and Joe Berke: Two Accounts of a Journey Through Madness

Like Isherwood’s book on Ramakrishna, encountering this was one of those moments that felt almost uncomfortably far out. It gives an account of Barnes’ “breakthrough.” Mary Barnes’ ghost recently came back into my life as I befriended the charming Ninian Stuart on whose estate in Scotland she lived towards the end of her life.

R.D. Laing: Wisdom, Madness, & Folly

“The Divided Self” and “The Politics of Experience” are more informative of Laing’s ideas, but this is a great read full of his charm and wit. Furthermore, this is a copy signed by the man himself given to me by my dear friend Simon C as he dismantled his library. I read it long after writing “Retreat”. For that book I used Adrian Laing’s biography of his father “R.D. Laing – A life” which is more factual and comprehensive.

Communes.

Covering the hippies and agriculture inevitably meant reading a lot about the commune movement. As I point out in “The Garden”, bizarrely, the agricultural aspect of going back-to-the-land is completely ignored in the reams of literature about the movement.

W.M. Sullivan: The Dawning of Auroville

This lovely book, printed in dark orange, is a superb chronicle of the birth of Southern India’s Auroville, an alternative city.

The Findhorn Community: The Findhorn Garden

The Findhorn Community became famous for growing massive vegetables on their sand dunes. The founders believed that this was as a result of spiritual cooperation with plant spirits, “devas”. This book has beautiful, very evocative, black and white photography – but my copy is slightly ruined by some idiot’s underlining in biro.

Paul Hawken: The Magic of Findhorn

After reading Findhorn’s entry in the book “The Secret Life of Plants” – Paul Hawken, today a famous author and sustainability guru – took off from Boston, Massachusetts to just East of Inverness in the north of Scotland to document the life of the community there. This is a great telling of the tale.

New Alchemy Institute: The Book of the New Alchemists

New Alchemy was more like a scientific experiment in living sustainably than an actual commune. Funded by grants in that era of progressive politics – at the time none of the “Alchemists” lived on the site. This book is one of my all-time favourite “scores” on Amazon. It only cost a few quid for this exquisite hardcover book, more like an album, lavishly filled with wonderful photographs and fascinating articles.

Richard Fairfield: The Modern Utopian

The Modern Utopian was a magazine which covered the commune movement in the USA. Fairfield was its editor but also something of a roving reporter writing articles. It is an engrossing collection of primary research material that you can dip in and out of with ease.

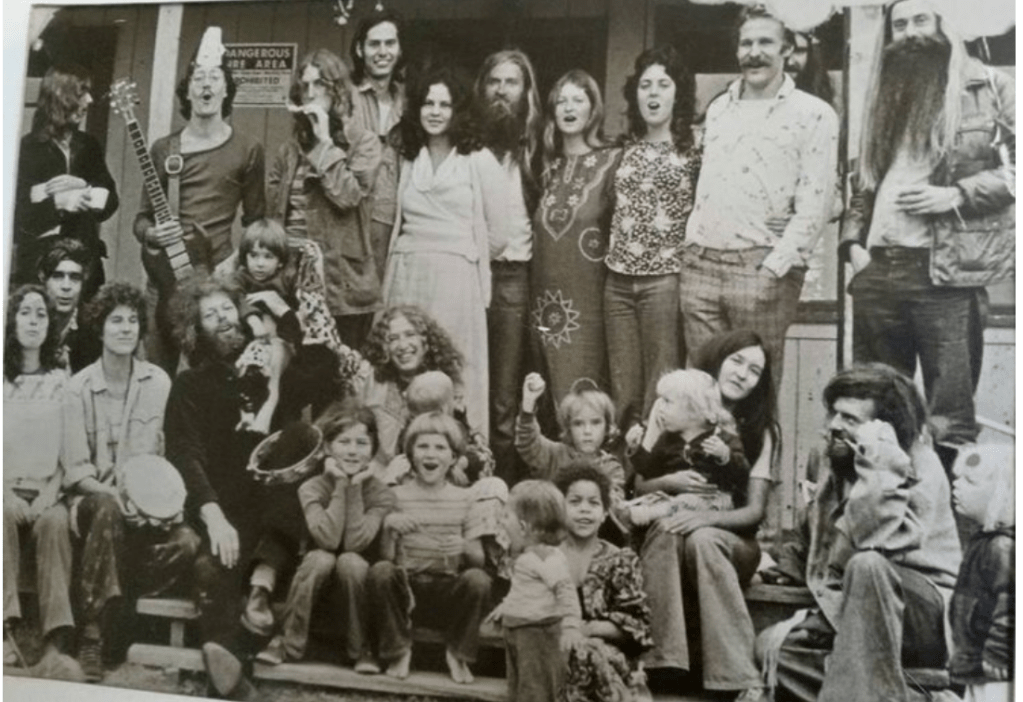

Ramón Sender Barayón: Home Free Home

An immense doorstop of a tome giving the history of the interconnecting fate of two of California’s most iconic communes: Morning Star Ranch – known colloquially as “Digger Ranch” a satellite of the Haight-Ashbury scene – and its successor Ahimsa Ranch, where many moved after the former was shut down for violation of zoning regulations.

Ramón Sender Barayón – known often as Ramón Sender – was a founder of the San Francisco Tape Music Center. A colleague of Steve Reich and Pauline Oliveros, he could equally have also gone into that brittle world of state-funded academic music – but instead plunged himself head-first into the hippie scene. First alongside Stewart Brand providing music for the Trips festivals – and then as an acid-fried communard – promoting his quite dubious habit of gazing into the sun.

Ramón brings together many different accounts from a wide host of contributors for this book, and weaves them all together beautifully. I particularly like it because this kind of material is never written down and dignified as history – it’s usually the doings of the rich and powerful. Yet this is precisely the sort of document of behaviour change that is essential to us as a species.

There are too many highlights to mention but the account given by Helen Mikul, a child growing up on Ahimsa Ranch, was the most far-out thing I read in the eight and half years of my research – and that’s saying something.

Stephen and The Farm: Hey Beatnik!

In “The Garden” I refer to The Farm as the Grateful Dead of communes. The largest in North America they grew all their own food and ran a raft of other businesses such as a midwifery team, soy ice cream manufacturer, and with their organisation Plenty even did charitable work in Guatemala. The Farm story is a major saga – one which continues to this day – and there are a whole range of books on it – but “Hey Beatnik!” is as good a snapshot of peak-era The Farm as you’re likely to encounter

Stephen Gaskin: Monday Night Class

The Farm was set up around the 6′ 5″ marine turned university lecturer Stephen Gaskin. Older than the hippie generation, Gaskin was fascinated by the LSD experience and, before he and his group went back to the land, in San Francisco he arranged the Monday Night Class of the book’s title. There he shared his take on psychedelics to a growing crowd of hippies. His ideas are heavily informed by Eastern philosophy. The book is a transcription of some of his talks and it’s great both for insights into “high” states of mind as it is as a magnificent period piece.

Whole Earth: The Last Whole Earth Catalog

Stewart Brand’s gigantic compendium of information deemed useful to the back-to-the-land generation is a gas. It’d be the perfect book to browse with your Hurricane Lantern as the snow piled up around your shack in the Green Mountains of Vermont.

Agriculture.

Perhaps you know all the books about LSD? Or the books about Eastern Philosophy? But this is where we might lose some people – but at the same time come across some new wide-eyed friends from the country.

Philip S. Callahan, Ph.D: Tuning in to Nature

Philip S. Callahan is the prophet of Paramagnetism. In that theory, the growth of plants is affected by magnetic and electrical currents. This has been largely dismissed as pseudo-science – it’d be a difficult thing to prove was having an effect. However, because it slots into other parts of Callahan’s thought, I’m less sceptical than I would otherwise be. That’s because his ideas around infra-red radiation are informed by his experience as a technical expert in radio waves.

Infra-red waves are electromagnetic waves which are longer than visible light waves, but not as long as radio waves. Humans can only see visible light waves of 380 to 750 nanometers. We can feel heat on our skin from infra-red radiation though. If you think about it, that posits the human skin itself as a kind of eye which is reading that signal. The ancestors of our eye were photoreceptor proteins which formed “eyespots” insufficient for vision, but able to distinguish between light and dark. These “eyespots” can be found on some snails.

Callahan argues that insects in particular have evolved antenna, essentially eyes different from our own, which are able to see into what is invisible to us. All manner of interesting phenomena make sense as a result – such as the similarity of insects’ antenna to radio masts, the appeal of stressed plants generating infra-red radiation to insects, and their communication systems among one another on that band.

Coming from a study of Eastern Philosophy, and its ideas of the existence of a total consciousness of which we are only able to usually see a partial glimpse – these ideas really resonated with me. The brain, perhaps another kind of eye – still on its evolutionary path to receive higher signals – is often conceived as a receiver too (rather than purely a repository of stored data). Imagine if with the stirrings of spirituality, which trouble people mostly today as mental illness, our brains were at a historical phase akin to the snail’s eyes which can only detect the presence of absence of light? If the brain were to evolve perhaps we might sense a richer spectrum – just as our eyes can see in such detail?

“Tuning into Nature” is another of these on-the-face-of-it “niche” books which proved to be totally mind-blowing. I read it as I was taking refuge at the Samye Ling monastery in the Scottish borders – a far out mission of its own.

Wendy Johnson: Gardening at Dragon’s Gate

Johnson is the ordained Buddhist priest who for many years picked up Alan Chadwick’s baton and worked the gardens at Green Gulch Farm – like Tassajara another satellite of The San Francisco Zen Center. In case the presence of all these Zen Buddhists in California sounds strange to a European looking at the Mercator projection of the globe – remember that if you keep traveling West from San Francisco you end up in Japan. I tried hard to contact Wendy Johnson to talk to her for “The Garden” but never made the connection. This is a gentle, beautifully assembled book describing her practice, inspired by Zen Buddhism, growing vegetables.

Sim Van Der Ryn: The Toilet Papers

Governor Gerry Brown appointed Van Der Ryn – who died very recently in October 2024 – as state architect for California. He promoted ecological values and was famous among the back-to-the-land generation for this commune classic which championed the careful recycling of human excrement. This idea, common in the Far East historically for four hundred years, was more recently explored by Joseph Jenkins in his “The Humanure Handbook.”

The more you read about – done carefully with untainted poo composted thoroughly – it makes complete sense and should be widely adopted. Unfortunately, widespread use of antibiotics, other drugs, and the terrible processed garbage people eat makes it harder to justify.

Wendell Berry: The Unsettling of America

Wendell Berry could be described as an agricultural theorist. His thinking is radical, wildly futuristic, and so far removed from the urban intellectual consensus that it registers as a shock when you first encounter it. I’m not going to try and summarise it here as it wouldn’t do it justice. “The Unsettling of America” is recognised as Berry’s classic but all of his books, and his poetry, are of the highest calibre.

Masanobu Fukuoka: The One-Straw Revolution

The legendary Buddhist farmer Fukuoka would summarise his approach to growing plants as “doing nothing.” His is an approach of non-intervention – of working, yes, but relying on natural processes. One of the hallmarks of Westernised behaviour is that people seek to mediate all their behaviour. They will rarely trust in natural processes. Fukuoka did have his own artificial hacks – like sealing seeds in balls of clay so they weren’t eaten by birds – but these are designed ultimately to hitch a hide with mother nature. Just as with Wendell Berry’s writing (Berry worked with Larry Korn to render the sensei’s ideas into English), Fukuoka turns the existing world on its head, and was of the opinion that “if 100% of the people were farming it would be ideal”.

Larry Korn: One-Straw Revolutionary

I would have LOVED to be have been able to interview Larry Korn, but sadly he passed away in 2010. There’s no question that Fukuoka’s ideas were his own, but Korn – a hippie – single-handedly popularised them. “One-Straw Revolutionary” is the perfect complement to his sensei’s own book.

Peter Tompkins and Christopher Bird: Secrets of the Soil

The voluminous sequel to their “The Secret Life of Plants” is remarkable. If it could be accused of being superstitious in places, it is not totally bonkers. More remarkable, however, is that a popular market for such a book existed.

Jeanie Darlington: Grow Your Own

A gorgeous, tiny book by an urban grower from San Francisco published in 1970. The seed of much more that was to come.

Rachel Carson: Silent Spring

Carson makes a powerful, measured argument against the use of chlorinated hydrocarbons. A beautifully-written book with, if it’s not too trivial to mention, beautiful illustrations.

Louis Bromfield: Pleasant Valley

A Pulitzer-prize-winning novelist and successful Hollywood scriptwriter, Bromfield used his fortune to return to the Ohio countryside from which his father’s family had had to abandon, and set up a farm. Bromfield, who visited Sir Albert Howard when he was working in India, was an early protagonist of sustainable farming techniques. The book conjures a dreamy farm of the imagination.

Albert Howard: The Soil and Health

There are a number of foundational texts for organic agriculture – but much of them derive from Howard’s ideas, and this book is their finest exposition. It lays out the organic formula: a healthy soil creates healthy plants, which bestow that health on the animals and humans that eat them. In the case of animal products, that health passes into the meat, dairy, or eggs we eat.

Recent critique has sought to tarnish Howard’s reputation – accusing him of possessing a colonial mindset. Having examined all the available information I feel that this is unjustifiably harsh. Sadly, none of us are immune to all the prejudices of our day. We can do our best and hope that history judges us kindly.

Rudolf Steiner: Agriculture Course

The Anthroposophist Steiner’s relationship to farming is somewhat like that of the Buddhist Fukuoka’s. A similar parallel might be drawn in the way that George Ohsawa and his philosophy relate to diet. Unlike this generally, religions don’t tend to get deep into the nitty gritty of these subjects.

In the Bible there are some tiny snippets of practical farming advice. There’s a little bit in Exodus about resting land, “For six years you shall sow your land and gather in its yield, but the seventh year you shall let it rest and lie fallow”, in Leviticus there’s something about allowing trees to grow before cropping them, “When you come into the land and plant any kind of tree for food, then you shall regard its fruit as forbidden. Three years it shall be forbidden to you; it must not be eaten.”, and in Matthew, Jesus makes the following observation pertinent to Natural Farming, “Look at the birds of the air: they neither sow nor reap nor gather into barns, and yet your heavenly Father feeds them.” In contrast, an interesting lady I met recently called Sara Moon informed me that the Hebrew Tanakh is full of farming advice.

However, in contrast Steiner comes with precise instructions: for example, burying horns stuffed with cow manure, then mixing the resulting material in a specific manner in water. These techniques which are the substance of the Biodynamic agriculture must have been peasant wisdom picked up by Steiner in the rural Austria of his childhood.

Permaculture.

Bill Mollison: Travels in Dreams

At 863 pages the Permaculture co-originator’s autobiography is immense, the biggest book here. Indeed, having finally found a reasonably-priced copy, for a long time I hesitated to tackle it.

Mollison had a wild and busy life before he met his younger colleague David Holmgren. He worked in the Tasmanian bush and on fishing boats before becoming a field biologist performing surveys. That led, finally, to work in academia. Accordingly, the first 615 pages of this book which cover these hi-jinx are astonishing and full of almost unimaginable peaks and troughs, terrors and delights. There’s no question about it, Mollison was a stone-cold legend…

But did he have anything to do with coming up with the idea of Permaculture? The theoretical Mollison which appears after page 615, where he airs his own ideas, is, I’m going to be honest with you, an embarrassment. Furthermore, there’s almost no commentary whatsoever about the work he and Holmgren did together working up Holmgren’s student thesis which defined Permaculture. It is brushed over in one sentence.

Certainly Mollison, a hugely knowledgeable man, was able to work up elaborate frameworks within the Permaculture concept. But did he come up with the underlying idea of designing systems which were organised around strategically harmonising efficiencies? Even as he tries to claim the thought had come to him many years before, and noting that his work as a rabbit trapper on ravaged estates caught the student Holmgren’s attention as it demonstrated his ideas, the answer based on the evidence of this book must conclusively be not.

As I see it, Holmgren was brutally ripped off, but nevertheless has been incredibly kind and generous with his support for Mollison and his legacy. Certainly, even if did steal the idea, it was Mollison’s egomaniac drive and rhinoceros-hide-resiliency which propelled the concept into the world.

David Holmgren: Permaculture. Principles & Pathways beyond Sustainability

This, on the other hand, is a masterpiece of rigorous conceptual thinking. For all its precision, clarity, and high-mindedness it is a very entertaining read.

Anthropology.

Anthropology being the scientific study of humanity. The diversion into these texts came on the tail of “The Garden”, just as with “Retreat” I found myself researching Telepathy and Psychokinesis on the back of reading so much about LSD and the Universal Unconscious. One reason for this research extension was because many of the ecological solutions to sustainable farming came from indigenous peoples – the Californian Indians, the Aboriginal peoples of Australia, the African farmers enslaved and brought to the New World to work, and the pre-Colombian pioneers of Terra Preta.

Edward Abbey: Desert Solitaire

Abbey didn’t have a huge association with the counterculture (maybe more so with his novel “The Monkey Wrench Gang”), and even less to do with health or farming. But in the literature I read which constellated around Thoreau’s “Walden” and Aldo Leopold’s “A Sand County Almanac”, his writing and this book kept being referred to.

A study of living alone in nature, “Desert Solitaire” is, in spirit, like the section of Kerouac’s “The Dharma Bums” where Jack works as a fire lookout. The stretch Abbey spends working as a park ranger on the Colorado Plateau has a similar feel. However, the difference is that the stunningly knowledgeable Abbey brings the desert’s ecology vividly to life. Not only that, he recounts both the extraordinary stories of prospectors moving to the area, and criticises the banal day trippers in their automobiles who drive in and out of Arches National Park.

Colin Turnbull: The Forest People

I’d come across Colin Turnbull before because, a student of Pygmy music, I have three of his field recordings on the Folkways and Lyrichord labels. Turnbull, a pioneer in his field, spent three years living with the Mbuti pygmies in what is now The Democratic Republic of the Congo. Although this book is part of his academic work, it is a genuinely accessible rendition of it. The book is full of stories which linger with one, such as his account of leaving the forest with one of the pygmies, and relating their observations of life outside of it.

I was led in turn to read Turnbull’s later disciple, Louis Sarno’s book “Song From The Forest” – also a very interesting book – but even to me, hardly the most politically-correct individual, full of the author’s questionable behaviour.

John G. Neihardt: Black Elk Speaks

One of William Burroughs’ favourite books. The descriptions of the aggression against the Sioux which are recounted here by Black Elk are horrifically vivid. I noticed criticism of Neihardt’s interpretation, so also read the supposedly more authoritative book “The Sixth Grandfather”. I’m sure it’s there, but I didn’t notice undue corruption – and “Black Elks Speaks” is a better read. I found this copy in a record store in Brooklyn.

Mircea Eliade: Shamanism

To my intense frustration the propaganda around psychedelics, driven at root I believe by people seeking to capitalise on the chemical’s absorption in the pharmaceutical mainstream, has redrawn the history around a number of important matters. The silly idea that Plato was “a tripper”, and the absurd fabrications around the Ancient Greek Eleusinian Mysteries are contemptibly stupid. I also find it galling that Shamanism is now, too, indelibly associated with psychedelics. Mircea Eliade was very clear in this foundational classic that the use of these drugs in Shamanism was a degeneration of the original traditions. I don’t even mind psychedelics so much – and I don’t begrudge anyone their enjoyment of them – but these corruptions obscure the fact that such alternative psychiatric states are part and parcel of all our make up.

Self-help.

As a genre it has a bad reputation for promoting egocentric and capitalistic behaviour. However, many of the classic books of the oeuvre such as Napolean Hill’s “Think and Grow Rich” and Maxwell Maltz’s “Psycho-Cybernetics” are very interesting. More recent interventions like Neem Karoli Baba follower Daniel Goleman’s “Emotional Intelligence”and Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi’s “Flow” issue closely from the kind of terrain we’ve been traversing. While others like Jack Kornfield’s “After the Ecstasy, the Laundry”, Osho’s “Courage”, and Thich Nhat Hanh’s “Miracle of Mindfulness” come directly from Buddhism.

Dale Carnegie: How to Win Friends and Influence People

How? Carnegie’s surprising answer, be a kind and generous person.

I learnt a lot in these eight and a half years searching.

My books “Retreat”, “The “S” Word”, and “The Garden” are excellent summaries of this field of knowledge, in which the counterculture is merely a motif. The terrain connects together like the continental plates once conjoined in the land mass of the planet earth. If you enjoyed this Sick Veg 100 please buy my books.

TLDR: Over time I have whittled all this knowledge down to two “answers”, which I found.

1) The principle of what I call “integral” and “etheric”, and the gradient between consciousness being grounded on the one hand, and dissolved into the unified field on the other. This is what the Vedanta means by the Sanskrit expression “Tat Tvam Asi” – “Thou art that.”

2) The possibility of living here on earth in alignment with that heavenly unified field; achieved by striving for what Buddhists call Right Livelihood. This entails being friendly where possible. Notably, it has an ecological aspect in terms of eating biologically grown food, and returning non-toxic organic matter to the soil. Furthermore, it underscores the importance of the healthy ego – far too much emphasis is placed today on ego dissolution.

If you can get your head around these two, and take my word for their importance, you’ll save yourself a lot of time reading.

By Hollow Earth at November 22, 2025

Labels: Art, Counterculture, Gardening, Growing, Science, Spirit

You must be logged in to post a comment.